The protest against arbitrary reforms to the Nicaraguan Social Security Institute (INSS) ignited the spark for a civic insurrection unprecedented in the country’s recent history. Students, workers, homemakers, and ordinary citizens took to the streets on their own. It wasn’t just about pensions, it was the product of years of pent-up authoritarianism, the exhaustion of the Ortega model, and a generation of young people tired of keeping quiet.

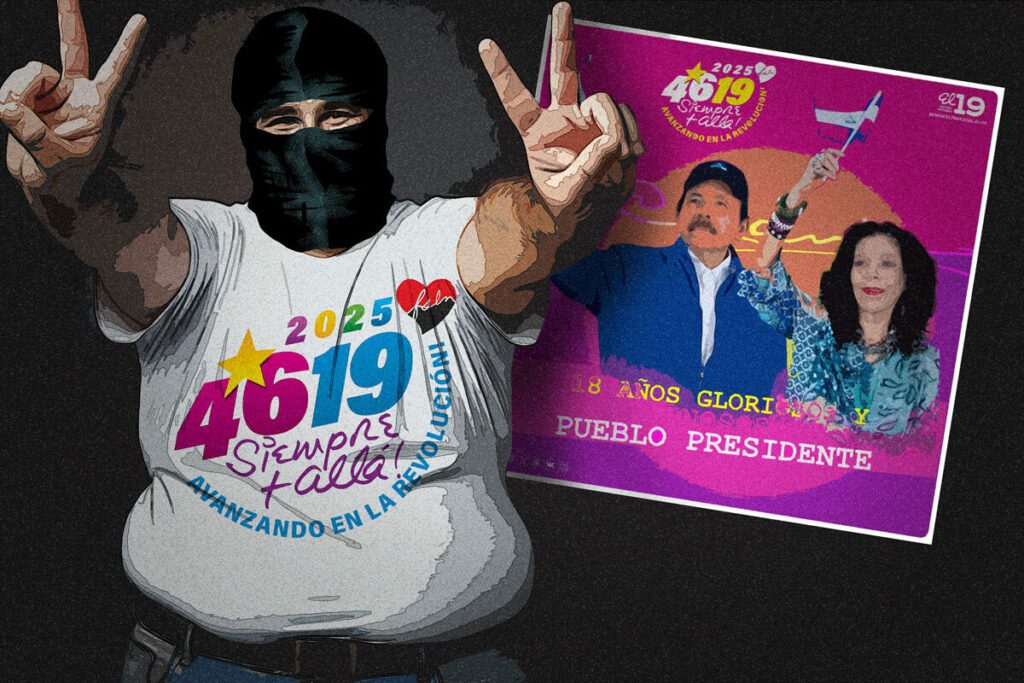

But the regime, led by Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo, had no intention of backing down or opening dialogue. The response was immediate and brutal: snipers stationed on rooftops, paramilitary forces, and police ordered to shoot to kill peaceful demonstrators. The crackdown left a tragic toll of 355 people killed, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

Seven years later, the country that dared to speak out is unrecognizable. Mass protests have been replaced by the exile of over 850,000 Nicaraguans; critical universities by centers for political indoctrination; freedom of expression by censorship; and civil society by a list of more than 5,400 shuttered organizations.

Citizens Without a Country, Without Rights

For human rights lawyer Juan Carlos Arce, the country is experiencing what he describes as a “civic death,” a condition imposed by a regime that has stripped people of their legal capacity to exercise their most fundamental rights.

“It’s the outright denial of people’s most basic rights. In the case of this dictatorship, that denial extends to all rights: civil, political, and even social, like access to social security, employment, and healthcare. It turns people into stateless individuals within their own country,” Arce explains.

The regime’s total control makes no distinctions, not even among its own supporters. “Not even its allies are spared from this total denial. The dictatorship has assumed the authority to decide who is allowed to enter or leave the country, denying internal criticism and with it, freedom of expression,” the expert warns.

Since April 2018, Nicaragua has undergone a steady, escalating process of state repression, dismantling its citizens’ fundamental rights. In its latest report, the UN Group of Human Rights Experts identified four clear phases in this institutional and social breakdown, reflecting a strategy planned and executed from the highest levels of power.

A Timeline of Repression

The first phase, from 2018 to 2020, was marked by violent, indiscriminate repression against citizen protests. According to the report, the National Police, the Army, and paramilitary groups carried out acts that could constitute crimes against humanity: extrajudicial executions, arbitrary detentions, torture, and enforced disappearances.

In 2021, during the second phase, repression became even more selective and strategic, aimed at securing Ortega’s reelection. That year saw mass arbitrary arrests, rigged trials, and the elimination of any political competition. The Supreme Electoral Council, controlled by the regime, revoked the legal status of opposition parties, while presidential candidates, business leaders, social activists, and journalists were imprisoned without due process.

In 2022, ahead of the municipal elections in November, the regime ramped up its efforts to wipe out any remaining opposition. This third phase saw the arrest of opposition mayors, persecution of their families, and open repression against the Catholic Church. Private universities, NGOs, and grassroots organizations also fell victim to a systematic dismantling of the country’s social fabric: thousands lost their legal status, their facilities were confiscated, and spaces for critical thinking were shut down.

The fourth phase, which began in 2023 and continues today, represents the consolidation of totalitarian control. According to the experts’ report, the regime has implemented measures to erase any form of dissent and reinforce its absolute hold on power.

“The authorities formalized their control through constitutional and legislative reforms, culminating in a sweeping constitutional overhaul now in force,” the report states.

The Legal Framework of Ortega’s Regime

Through this new OrMu constitution, the dictatorship formalized its grip on the state’s institutions. It has also intensified repression by stripping citizenship from dissidents or those it labels a “social risk,” confiscating their property, expelling them from the country, and barring the return of anyone not aligned with the official narrative.

Arce says the repression continues today through constant surveillance, harassment, arbitrary arrests, and enforced disappearances, while the dismantling of what little remains of civic space accelerates. He notes that the regime has unleashed a barrage of repressive policies, ranging from the use of military-grade weapons against protests to legal reforms designed to strip citizens of their fundamental rights.

Among these, he highlights the elimination of Article 46 of the Constitution, which had incorporated international human rights treaties, and the total subordination of the judiciary to the executive branch. “All of these actions are essentially arbitrary, designed to leave citizens utterly defenseless against abuses of power,” he concludes.

The World Acknowledges Ortega’s Totalitarianism

Feminist activist and former political prisoner Tamara Dávila says what exists in Nicaragua today is an absolutely totalitarian dictatorship, widely recognized by the international community.

“After seven years and all the atrocities committed by the regime, no country or international body, including UN and Inter-American human rights mechanisms, can deny that the dictatorship in Nicaragua is utterly totalitarian,” Dávila asserts.

She explains that the regime’s totalitarian nature extends beyond politics, infiltrating basic rights like healthcare and education, two pillars of human development now contingent on political loyalty in Nicaragua.

“There isn’t a single independent institution or civil society organization left. Not a single independent news outlet inside the country. Both civil society organizations and media outlets have been confiscated, shut down, and dissent or critical thinking in either sphere has been outlawed,” Dávila emphasizes.

The North Korea of Central America

For student leader Lesther Alemán, the situation in Nicaragua can only be compared to an extreme authoritarian model like North Korea. “We’re dealing with a marital dictatorship, a one-party dynasty project centered around two figures: Ortega and Rosario. In this context, surviving political persecution and pressure is already an act of resistance,” says the exiled youth leader.

Alemán describes a system built on ideological indoctrination, political persecution, and impunity as the cornerstones of its grip on power.

“A policy of widespread impunity, imprisonment or exile for anyone who opposes or lacks ties to them, persecution of independent journalism, and indoctrination through every state institution, it can only be described as a dangerously totalitarian model destabilizing for the region,” he warns.

He also points to a progressive shift within the regime’s authoritarian power structure, moving from Ortega’s symbolic authority to the growing dominance of Rosario Murillo. “We’re witnessing a transition from the political mystique and symbolism of Daniel Ortega to Rosario Murillo’s consolidation of control. She’s now focused on creating new leadership figures loyal to her and tightening the regime’s grip as a family-run state.”

As an example, he cites the recent appointment of “volunteer police officers” pledging direct loyalty to Murillo, a measure that reveals both control and internal distrust.

A Vulnerable Regime

In Alemán’s view, April 2018 marked an irreversible turning point, signaling the political, ideological, and symbolic defeat of Sandinismo.

“That historic April moment also redefined political engagement, allowing historically excluded sectors to take part in decision-making and become part of the national landscape. It was a failure for the entire rotten political class that existed before 2018,” Alemán says.

Despite the regime’s absolute control, both Alemán and Dávila believe Ortega and Murillo are now in their most vulnerable phase. They trust that persistent civic resistance, both inside and outside the country, will eventually open a path to democracy.

“I firmly believe there’s still hope to end this dictatorship. Much of that will hinge on their continuous mistakes. But for the opposition, which includes every person opposing this regime, the responsibility is to rally international support to economically and diplomatically isolate the dictatorship. And the international community still has actions to take,” says the student leader.

“I’m committed to that transformation, just like so many others I work with. We’re going to achieve it, because I want a different Nicaragua for my daughter, and that’s my promise,” says Dávila.

She also believes the dictatorship is increasingly isolated, both within the country and internationally. In this context, recent economic sanctions and tariffs imposed by the United States open a new scenario in which, according to Dávila, the Ortega-Murillo regime “has no other alternative, no cards left to play, except to open the door to a democratic process.”