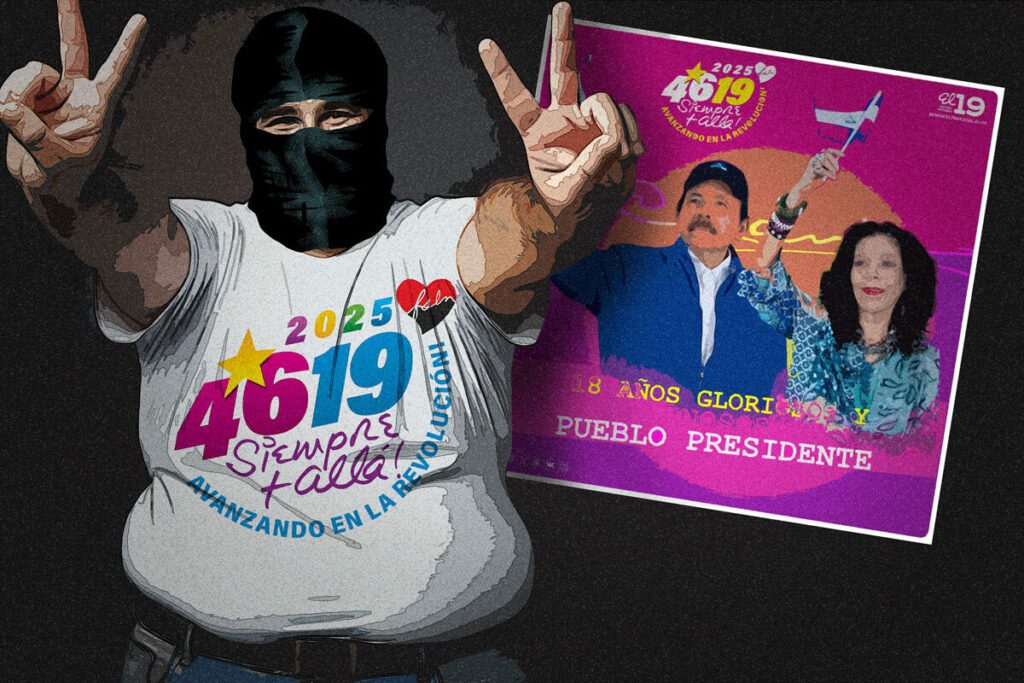

On Wednesday, February 26, Rosario Murillo declared herself the commander of Nicaragua’s paramilitary forces. That day, the Sandinista co-president officially swore in more than 30,000 “volunteer police,” dubbing them “warriors” and “defenders of peace.” Wearing balaclavas to shield themselves from public scrutiny, these men and women were formally recognized on national television as an “auxiliary force supporting the National Police,” effectively making them the country’s third legally sanctioned armed group.

The “volunteer police” stood for hours without drinking water. They weren’t allowed to remove their masks, no matter the heat. Official TV footage captured their sunburnt, weary eyes—but no one complained, at least not publicly.

While their balaclavas made it hard to identify who these “volunteers” actually were, some social media users managed to do just that—exposing everyone from a judge in Matagalpa sworn in earlier that month, to public employees recognized by former coworkers.

These 30,000 hooded figures weren’t chosen at random. Months earlier, the Ortega-Murillo regime had ordered public workers and Sandinista loyalists to attend survival and police training camps in Nicaragua’s mountains.

In September 2024, DIVERGENTES reported how the dictatorship—coordinating with the National Police, political secretaries of public institutions, and officials from the Ministry of the Interior—forced government employees to attend military-style camps in preparation for a possible coup attempt.

Public workers were sent in groups to remote areas with minimal food and water, subjected to grueling drills meant to “build character.” “Some fled the country for fear of being registered as part of a new armed group. Others stayed and agreed to become ‘volunteer police,’” explained a security expert interviewed for this report.

“The Ortega-Murillo regime has spent months consolidating a third armed force that essentially answers to Rosario Murillo. Maybe it’s because the police still see Daniel as the only leader, or because the military never accepted her due to her authoritarianism. Either way, with this act, she publicly crowned herself leader of the paramilitaries,” the expert added.

A source from the Ministry of the Interior said that although this third armed group appears strong, it’s “volatile,” and unlikely to show unwavering loyalty. What is clear is that most members—whether public workers or hardcore Sandinista loyalists—joined the force out of allegiance or in exchange for regime favors.

“This group is all about service. Some are public officials in positions of power thanks to Murillo. Others are Sandinista Youth members, neighborhood operatives, or pardoned convicts repaying their debt to the regime. And of course, there are state employees who joined simply because they need to put food on the table,” said the ministry source.

DIVERGENTES spoke with some of these masked individuals and compiled brief profiles. Their testimonies revealed four main types: public workers, Sandinista militants, ex-convicts, and true paramilitaries—those who acted as shock troops for the dictatorship in 2018, firing to kill during civilian protests that left more than 300 dead.

The Pardoned Man

Adonis walks through brush, searching for a wild rabbit. He’s been at it for over half an hour without luck. On the other end of the line, we wait patiently for him to answer—just as we agreed five days ago. Finally, the 25-year-old pauses to catch his breath and greets us cheerfully. He apologizes for the delay.

“I told my uncle it was fine, that I’d share my story. Just don’t use my real name, okay? You know how it is—we owe everything to the party,” says the young man from a small town in Granada, about 42 kilometers from the capital, Managua.

Adonis is a volunteer police officer. He says it plainly, without hesitation. He claims he serves the homeland and the presidents because “they give the orders, and we follow them.” He decided to join the “peace warriors” just before signing his release order in 2024. That’s right—Adonis is a former inmate pardoned by the Ortega-Murillo regime, despite having served only one of the four years he was sentenced to.

He won’t talk about his crimes. Says he’s changed. That the regime gave him a chance—on one condition. To walk free, he had to sign a behavior agreement and agree to become a volunteer police officer. They didn’t put it in those exact words, but he figured it out soon enough.

“I got out of prison thanks to God—and my good behavior. The government helped me and said they’d keep an eye on me, because I could be a valuable asset. A few weeks later, the political secretary from my area contacted me about some special training, and then told me I’d be joining the volunteer force,” he explains.

That “special training” was part of the regime’s police camps, typically meant for public workers. Unlike many of them, Adonis feels grateful—and hopeful he’ll land a job down the road. He completed the training and waited for his call-up.

Meanwhile, he started working at a neighbor’s farm—a man he affectionately calls “uncle.” Gustavo, 54, has always liked him. He doesn’t excuse the crimes Adonis was convicted of—he actually thinks the punishment was necessary. But now that he’s out, Gustavo sees a change.

“Young people need guidance. I believe he can move forward without falling into old patterns. I just don’t like that police volunteer business. You know how dangerous those people can be—what they might ask him to do. Let’s hope they don’t drag him into something nasty,” Gustavo said, also requesting anonymity.

Adonis got the official call at the end of January and was sworn in during the February ceremony in Managua. He traveled from Granada with other ex-convicts and public employees. He says he recognized some faces from his time in prison.

“I see this as a second chance. I don’t think helping the police is a bad thing—not with all the bad people out there. Sure, maybe I was one of them once, but that’s in the past. I’m someone else now. I want to do things right,” says Adonis, who now splits his time between his volunteer duties and farm work—the only job he could find from the one neighbor who doesn’t fear him.

Our call with Adonis lasts just twelve minutes. He asks again that we not identify him—he knows how things work in this country. Before we hang up, we ask what he thinks about the origins of the volunteer police and their role in the 2018 protests.

Adonis pauses. Back then, he was 18. He admits he marched to defend pensioners, but stopped once things “got political.”

“Back then, a lot of things were done wrong. But that was another time. Things are different now. I’ve changed. Thanks for the interview,” he says, then ends the call.

A few minutes later, we message him on WhatsApp to check if our question bothered him. He replies saying everything’s fine—he just got a little tense, but he’s okay with his story being published.

The Political True Believer

Among the 30,000 volunteer police sworn in by Rosario Murillo on February 26, one stood out for his devotion. His name is Roberto, an administrator at a municipal office under the Ortega-Murillo government. He was happy for two reasons: first, for the sense of duty that comes with being a volunteer police officer; second, because the public event was finally over.

“Man, we were standing for half the day, no water, sun beating down on us. I respect the compañera, the comandante, and I’m proud to be part of the Volunteer Police—but I was exhausted… I didn’t get home until after midnight. Still, I think it was worth it,” Roberto told DIVERGENTES.

Roberto, a nearly 50-year-old Sandinista loyalist, agreed to speak under two conditions: anonymity and the chance to explain why he chose to become a volunteer. We respected both.

“I was born into a Sandinista household,” he says firmly. “And the only ones who’ve ever helped the people are the Sandinistas—no one else.” He’s worked for the state his whole life, in various offices. Though he says he hasn’t received the same perks as others, he’s grateful for steady work. So when they offered him training in the mountains and the chance to become a volunteer officer, he didn’t hesitate.

The offer came from the political secretary at his municipality. They said he had potential to serve as an auxiliary force for the police. Roberto believes they valued his loyalty—especially because he never stopped working for the state. He also hinted at his involvement in “cleaning up” the streets in 2018.

He doesn’t elaborate. Just says he “did nothing wrong,” and points to today’s “peace” as proof it worked.

“I believe in serving the people. That’s why I joined the Police—to help prevent more violence, more crime… more darkness,” he says, echoing the rhetoric of Sandinista neighborhood activists.

Roberto says that, like him, many in the volunteer police force signed up out of a sense of duty. In his office, most volunteered willingly. Those who didn’t, supposedly, weren’t forced.

“There’s a woman in another department who said no—said she didn’t feel called to join. The political secretary didn’t threaten her or pressure her… she’s still working, just like the rest of us,” he concludes.

The 2018 Paramilitary

The first time Daniel Ortega used the term “volunteer police” was to refer to the paramilitaries who attacked peaceful protests in April 2018. At that time, the dictator justified the presence of this armed group as an additional tool for the National Police to carry out the violent “clean-up operations” across the country.

The men Ortega identified as volunteer police wore blue shirts, carried assault rifles, and wore balaclavas. International organizations, such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, recognized them as paramilitaries, an irregular armed force not recognized in Nicaragua’s Political Constitution.

“Paramilitaries didn’t cease to exist, even after the regime controlled the peaceful rebellion of April. Some were reassigned to other duties in different government offices. They remained there until this year, when they were once again called upon,” explains the security expert interviewed for this article.

According to the expert, sooner or later the Sandinista regime would legalize the paramilitary figure, allowing them to operate under constitutional protection. While not using the same name, the group would function under the umbrella of volunteer police that Ortega’s government used since 2018.

DIVERGENTES asked a source linked to the Ministry of the Interior about the return of the paramilitaries to public life, but this time under a legal guise. The senior official explained that most of those who served in 2018 continue to do so, albeit with a low profile.

“The swearing-in of the volunteer police is a recognition of those who remained loyal since before 2018 and after that year. Not all those initially enlisted are present now, the number has decreased, but they are still waiting for orders as they did in April,” said the high-ranking official linked to the Ministry of the Interior.

DIVERGENTES attempted to contact one of the hundreds of masked individuals who participated in the 2018 clean-up operation and had been interviewed previously for other reports. Although they answered the call, they indicated they were not interested in sharing their story for security reasons.

“The volunteer police are not just made up of public employees; there are also JS (sandinista youth) members, people who were imprisoned, and FSLN fanatics. It is a segmented group that won’t be on the streets like the police but can repel any protest or denunciation attempt anywhere in the country at any time,” stated the security expert, who added that this armed group now has more access to information than before, as they have included militants who conduct investigative work in each municipality’s neighborhoods.

The Praying Man

On March 5, 2025, DIVERGENTES published the first profile of one of the masked men who formed part of the army of balaclavas sworn in by Rosario Murillo in February. It was the story of Justino, a public servant who didn’t want to join the paramilitary body of the Sandinista dictatorship but was forced to.

Justino, who requested to be called by this name to ensure his safety, works as a secretary in a public institution. He shared that he had never been summoned for these paramilitary tasks until February 25, when he received a call from an unknown political secretary of the Sandinista Front: “I was told to present myself at five in the morning at a certain location with my ID in hand and wear the following outfit: black pants, black shoes, and a white t-shirt,” he explained.

This profile explains how the public employees summoned to these mandatory military camps are mostly the lowest-ranked staff members: drivers, guards, orderlies, janitors… A marked classist tint appears in this Sandinista call-up, as middle and senior-level officials have not been asked to swear in as paramilitaries.Justino confessed that, to find solace amid the intimidation orchestrated by the regime, he recited Sor María Romero’s exorcism prayer, which he knows by heart. He, like the others revealed in this special report—even those who align with the Sandinista dictatorship—are victims of a system that forces Nicaraguans to live in violent and dangerous social environments for everyone, regardless of political ideology.